REMIX. Discover 800 years of art

until February 2025 at the Museum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte, Dortmund

With REMIX. With Discover 800 Years of Art, the largest art collection in the region can be enjoyed in new constellations. The exhibition presents the treasures of the MKK in an entirely new display and invites you on a fascinating journey through the centuries in the large exhibition hall.

From the Middle Ages to Jugendstil

Paintings and sculptures from 800 years of visual art are brought together on an area of 800 square metres – from medieval Romanesque art to Jugendstil. Highlights include works by Conrad von Soest, Caspar David Friedrich, Constantin Meunier, Anselm Feuerbach and Lovis Corinth. Immerse yourself in art history in rooms devoted to individual epochs and experience how art reflects cultural and historical developments. Discover attitudes and outlooks on life in images that reflect how their artists saw the world: from the spiritual Middle Ages to the early modern period, which explores the outside world, and from Romanticism’s withdrawal into the inner sphere to Realism’s renewed focus upon external reality.

Compact and variable

REMIX presents a slice of Central European art history in a compact overview. Between now and 2025 the display will be remixed several times, in order to explore the full wealth of the MKK’s art collection and thereby showcase ever new aspects – including photographs, prints and drawings, too.

In short audio clips, Christian Walda, art historian and curator of the exhibition, examines how art reflects the world in which people live and historical developments.

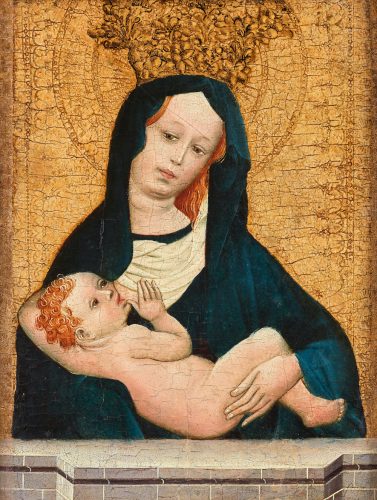

The Middle Ages – Heartfelt emotion

The Middle Ages are many different things. Lasting from the 6th into the 16th century, they span the period between antiquity and the modern era. A great deal happens during this long expanse of time. If we compare the Romanesque, somewhat stiff-looking bronze Crucified Christ from ca. 1180 and the Late Gothic wood Angel with the Instruments of the Passion from the late 1400s, we see how the human image has changed radically in three centuries alone: from a rigid figure to animated gesture.

The themes of art thereby remain largely the same across time: suffering, heartfelt emotion and fellowship. Medieval art in Europe is predominantly Christian. It revolves mainly around Jesus’s suffering, the tender relationship of his mother and others towards him (compassion and solicitude), and the relations of Christians to one another (fellowship, with their saints as role models). This art tells stories of the darkest depths of the soul and is strongly emotional and heartfelt.

Early modern period to Neoclassicism – The discovery of the world

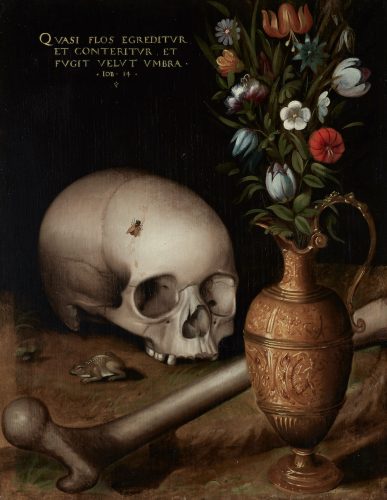

The lengthy timespan from the early modern period in the 16th century, via the Baroque and Rococo eras, to Neoclassicism around 1800, encompasses numerous very different stylistic epochs.Yet there is one thing common to the art produced between the spiritual Middle Ages and largely likewise inward-looking Romanticism: it is made in a social climate of discovery. The elite and intellectuals in Europe turn their attention to the outside world. It is the age of scientific discoveries – culminating in the colonisation and exploitation of the rest of the world.

In the Enlightenment, people increasingly assert their rights as individuals. Global influences and the greater interest in things lead art to become more diverse and its contents more secular. In the Netherlands and Flanders, in particular, entirely new themes establish themselves in painting, such as the still life, landscape and scenes from daily life. Modes of representation grow more varied, experimental and – above all in the Baroque era – dynamic.

Romanticism and Biedermeier – Retreat as advance

Intellectuals turn back to religion and look increasingly for emotion and fellowship, which they do not find in the Enlightenment with its demands for greater individual freedom. Romanticism and the Biedermeier period, with their withdrawal to the inner and the domestic spheres, are political and artistic reactions to this anxiety-laden time. Landscape now becomes the primary setting through which yearning and emotion can be expressed in painting. It is less a faithful likeness than a utopia.

The Düsseldorf School of Painting – Between ideal and reality

The Düsseldorf Academy under the direction of Wilhelm von Schadow represents the transition from emotional Romanticism to objective Realism. Although the artists of the Düsseldorf School of Painting are often still steeped in idealism, introspection and religious fervour, they increasingly seek the study of external reality. Landscape as a subject of painting in its own right comes ever more to the fore.

German art around 1830 is characterised by elements of Neoclassicism, Romanticism and Realism, which co-exist and mutually intertwine. This confusing complexity corresponds to the political situation: the emerging anti-feudal opposition is pitted against a reactionary authority that surfaces – unsurprisingly – in the religious art of the Nazarenes. The shifts towards Realism are also driven by the desire to compete with an entirely new rival in the world of art: photography, invented in 1826 by Joseph Niépce.

Realism – The discovery of everyday life

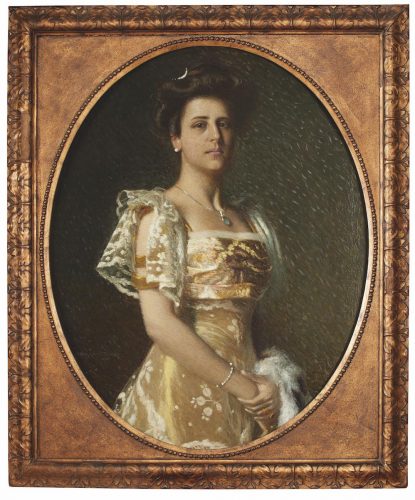

European art experiences two revolutions in the 19th century: firstly, with Realism around 1850, a revolution primarily in visual content, and subsequently, with Impressionism, one in painterly means. Realist art is characterised by an emancipation of its subject matter. Whereas pictorial themes have previously been ranked very differently in terms of value (a Christian scene has always counted for more than a portrait, and a portrait for more than a landscape), motifs now become equal in worth.

Realism is also called such, however, because the things of this world are represented more realistically. The art of Realism thus aims at capturing daily life and at objectivity. It is spurred on here by the example of its emerging competitor, photography. If we look behind this artistic development at the relationships with the world typical of the time, we can recognize the endeavour in the mid-19th century, after the inward-looking gaze of Romanticism, to open up again to the external things of the world.

Impressionism – Art as art

After Realism opened up painting’s content, Impressionism in the 1870s in France liberated its means of execution. The best-known German representatives are Max Liebermann, Lovis Corinth and Max Slevogt. Characteristic of Impressionism is its use of colour as the prime element: the paint is at times applied thickly, meaning that the painting remains recognisable as such and we can follow the artist’s process. The paintings thereby take on a dynamic effect.

Broad brushstrokes prevent clear delineations and finer details. Our brain is stimulated by this lack of clarity to complete the image, and since this depends on our mood at the time, the works appear animated and subjective. The artists working in an Impressionist manner no longer compete with photography and make a virtue of necessity: they now paint in a completely different way. The overt subjectivity of their paintings, which arises out of the rejection of photography’s precision, is the cornerstone of modernism.

Jugendstil – Art and life

Jugendstil, the dominant ideal of art in the German-speaking sphere from the 1890s until the First World War, is a sweeping movement of renewal. Its representatives want to bring aesthetics into people’s daily lives. In the firm conviction that a beautiful world fosters peace and civilisation, beauty in every sphere of life is the most important goal. Jugendstil is an international phenomenon, even if it manifests very differently in other countries.

Its commonalities include ornament (modelled on the forms of nature), the striving for functionality, the design of quotidian objects large and small (buildings, furniture, glassware, tableware), and the “life reform” (Lebensreform) as advocated by philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, for whom art represents the true and highest form of life. In the visual arts, these ideals find expression in the dignified movement of the figures and elegant representation of the individuals portrayed.

A look behind the scenes

This video forms part of the exhibition with its more than 110 objects on display. It sheds light on the complex, painstaking and varied work carried out by the museum’s conservators and the professional care with which they handle the artworks.